No Matter How Much Parenting Dads Do, Moms Somehow Do More

The child care arms race

I’m happy to announce that the writer who goes by the pseudonym Infovores (who I’ll refer to hereon as Info, for short) will be a regular contributor on Time Well Spent. Info writes on the Infovores Substack, which is one of the few Substacks I personally subscribe to. Him and I have also conducted a written interview recently where he asked me a battery of excellent questions, and I’ll link to it when it comes out tomorrow so you guys can get even more good stuff. The following is Info’s first post, and I hope you enjoy it as much as I did. Be on the lookout for even more mind-moving work in the future!

-Sotonye

You’d think that with men tripling their child care hours and family size dropping like a stone, the parenting gap would be pretty much closed. But somehow women found a way to ramp it up just as much. What explains this?

The most optimistic reading is that child care gets a bad rap. If both men and women enjoy spending time with their kids and rising living standards make that time more affordable, then of course they’ll do more of it. If that were the main story, I’d expect to see somewhat happier kids.

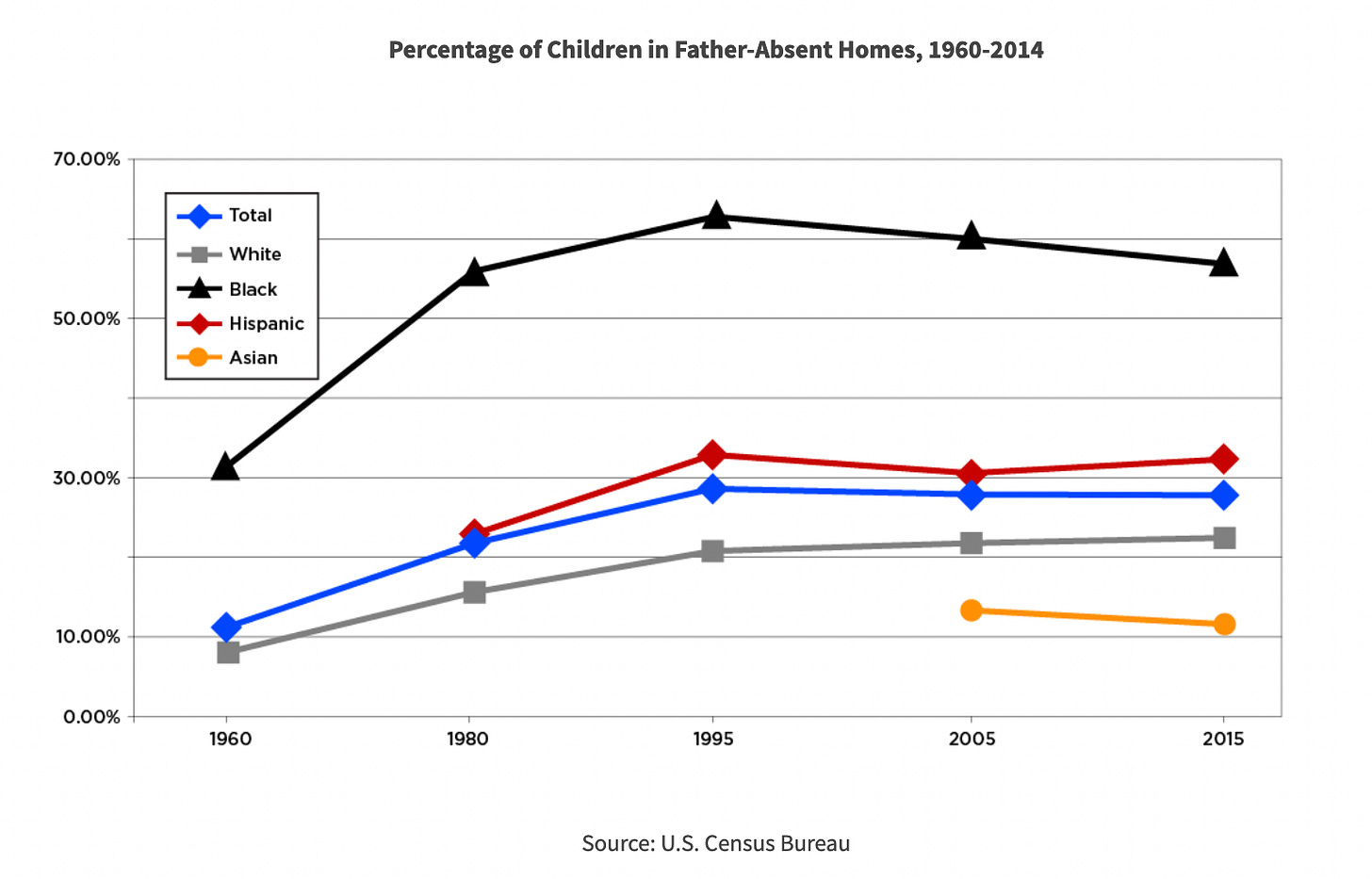

Or maybe Moms and Dads only appear to do more collectively due to a fallacy of composition. While it feels natural to add the average Mom hours to the average Dad hours, this is only technically appropriate if we assume that each family has one of each. Given the post-60s rise in single mothers and absent fathers (with the latter unlikely to show up in the data), this is sadly not likely to be the case.

But while the rise in single motherhood is a genuine crisis, these numbers can’t be fully explained by family breakdown alone.1 This brings me to my primary hypothesis—the child care arms race.

One of the most powerful motivators in human behavior is the desire for relative status. Whether in looks, salaries, or possessions we often compete fiercely to be at least a little bit better than our peers regardless of how much we have in absolute terms.

Since people tend to concentrate on competitions they are most likely to win, we would expect status motives to be especially powerful on this dimension for women within the household and for elite parents across households.

Within Household

Relative to their male partners, women on average possess several distinct advantages:

Greater warmth, sympathy, altruism, and sensitivity2

A preference for people over things3

Greater ability to read emotions4

Better sensory perception (e.g. hearing and smell)5

Better episodic memory6

All of these things contribute to women being able to supply child care at a more favorable cost benefit ratio than men. Thus when social pressure or greater means lead men to spend more time with their kids, women simply up their game to maintain their status as the primary caregiver.

Between Households

The arms race extends beyond the home front in comparisons between sets of parents. If the neighbor child goes to ACT camp, you can bet that my kid is going too. Then if he gets a full-time tutor, maybe I will too until…

Because this cycle can go on almost indefinitely for the wealthiest households (and modern elites are uniquely insecure), this subset of the population can easily push parental investment far past the point of diminishing returns. In addition to spending money on their children, status-hungry parents likely spend hours shuttling them between extracurriculars, coaches, and therapists in a way that past generations would have deemed certifiable. Anything to maintain an edge over the competition.

To illustrate, suppose that there were 10 mothers and 10 fathers in 1965 but only 5 fathers in 2015. If we multiply using the averages we see in the chart, total household childcare hours are 125 in 1965 (100M+25D) and 185 in 2015 (150M + 35D). This reveals a true aggregate increase of 48% (60/125). Though smaller than the 75% (9.5/12.5) increase obtained under the fallacy of composition, there remains a very sizeable jump.

As emphasized above, results in this list refer to statistical averages. There is a fair bit of overlap in the distributions of all of these traits, meaning that there are many men more (for example) warm than many women. Still, these average tendencies likely contribute to significant sex differences for the outcomes discussed in this post.

Now, back to your regularly scheduled footnote: See for instance Costa, Terracciano, and McCrae (2001); Del Giudice, Booth, and Irwing (2012); Falk and Hermle (2018).

Wright and Skagerberg (2012)

Joseph and Newman (2010), Table 6

Halpern (2012)

Herlitz and Yonker (2010)