Some Highlights From My Tablet Mag Article On SF’s Reparations Plan

Tablet asked me to report on the plan, it’s worse than you think

Tablet Mag asked me earlier this month to detail the San Francisco Reparations Committee’s plan to upend the city’s finances by, for one example, paying its qualifying black residents $5 million dollar lump sums for harms caused by racism.

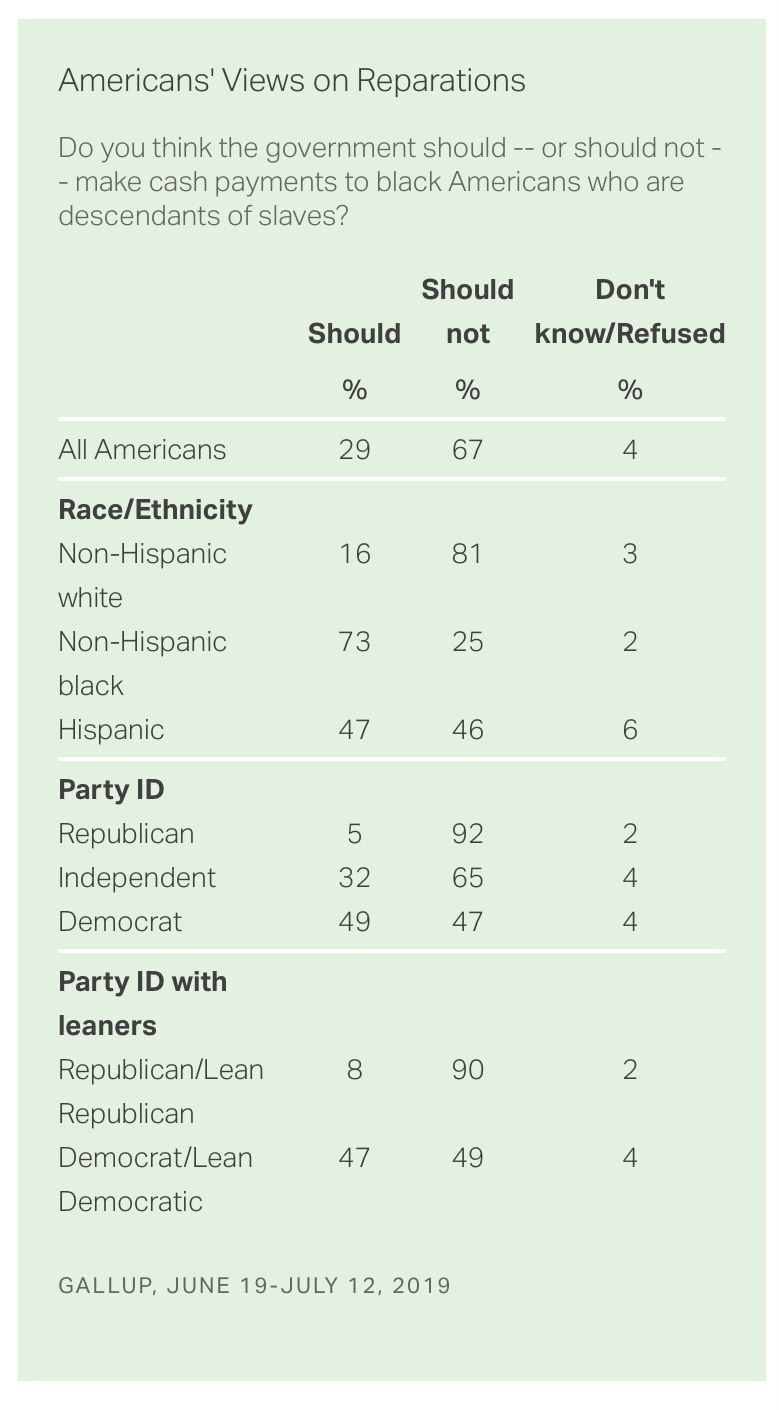

Reparations are a consistently unpopular political question—a Gallup poll from 2019 found that 67% of Americans oppose cash handouts as redress for slavery, which is not what I would have guessed considering the meteoric rise of Schmittian identity politics since Trump took office. Even Democrats are nearly evenly split on the matter:

Trust The Plan

The plan cites slavery as its meta-justification for reparations, which finds its relevant expression in Urban Renewal policies ushered in by FDR’s 1937 Housing Act. Urban Renewal was a large-scale effort to rehabilitate slums across the nation and improve living standards for poor Americans, one of FDR’s many reforms that profoundly reshaped the country.

The SF Reparations Committee acknowledges that California never actually had slavery, but describes the efforts of Urban Renewal to improve the slums in San Francisco as following in the same vein as the practice:

As the plan acknowledges, chattel slavery did not exist in San Francisco or California. The plan therefore tries to make the case that the “tenets of segregation, white supremacy, separatism, and the systematic repression and exclusion of Black people from the city’s economy” were codified in San Francisco’s urban renewal policies of 1948. Those policies included the creation of the San Francisco Redevelopment Agency(SFRA), California’s first redevelopment agency, which sought the rehabilitation of slums across the city. The agency was formed under California’s Community Redevelopment Act of 1945, California’s response to the Housing Act of 1937 passed by FDR. The Housing Act provided subsidies to municipal housing agencies with the goal of improving living conditions for poor Americans nationwide.

This is how the reparations committee describes the alleged harms of 20th-century urban renewal projects:

Of particular focus in this plan is the era of Urban Renewal, perhaps the most significant example of how the City and County of San Francisco as an institution played a role in undermining Black wealth opportunities and actively displacing the city’s Black population. As San Francisco’s African American population grew between 1940 and 1963, public and private entities facilitated the conditions that created near-exclusive Black communities within the city, while simultaneously limiting political participation and representation, disinvesting from academic and cultural institutions, and intentionally displacing Black communities from San Francisco through targeted, sometimes violent actions.

But the plan’s characterization of this history is incomplete and inaccurate, leaving out crucial details about the causes of these problems and the ways they have been addressed. The plan also privileges Black displacement while rendering the forced removal of the city’s Japanese and poor white residents invisible.

San Francisco’s urban renewal concentrated most of its efforts in the Western Addition district of the city—an area that many African Americans moved to following World War II. The Western Addition had previously been home to a large population of Japanese residents since the early 20th century—with nearly 600 Japanese businesses operating between South Park and the Western Addition by 1909.

The Western Addition’s Japantown, established in 1906 after the destructive San Francisco earthquake, had the world’s largest and oldest Japanese population living outside of Japan by 1940. But over 5,000 of those residents were forcibly removed after FDR’s executive order to intern Japanese families on the West Coast. This paved the way for Black San Franciscans to move in and turn the neighborhood into a cultural base. The Western Addition’s famous Fillmore district subsequently became known as the Harlem of the West, famous for its jazz and other clubs.

Following the internment of Japanese residents, urban renewal displaced nearly 5,000 more families in the 1950s and 1960s, around 40% of whom were white. The Reparations Committee does not call for reparations for these white families displaced by urban renewal, nor mention them in its plan. The plan also does not mention the displacement of Japanese families which made the historic Fillmore district possible, or call for reparations for these families. The plan does deign to mention that San Francisco compensated the small number of Japanese city employees for income losses during internment, as a supporting example of what the city could and should do for its Black residents.

Eligibility and benefits of the plan

Here we get into the requirements and the benefits of the plan, this is where things get wild.

According to the committee’s latest report, these are the main requirements for receipt of reparations:

Being an African American descendent of an enslaved person or a descendant of a free Black person prior to the beginning of the 20th century, or who has “identified as Black/African American on public documents for at least 10 years”

18 years or older

Born in SF or moved to the city before 2006

The plan goes on to state that, in addition to providing proof of the above eligibility requirements, proof of being harmed by the city of San Francisco must be provided. An example of the kinds of possible harm one could have experienced include being charged for a drug-related offense. “An individual, or direct descendant of someone, who was arrested, prosecuted, convicted, and/or sentenced in San Francisco for a drug-related crime and/or served a jail or probation sentence for a drug-related crime in San Francisco during the failed War on Drugs (June 1971 to present), including individuals who received offenses, or served, as juveniles.”

In addition to the $5 million lump sum payment the plan proposes for each eligible Black resident, the plan presents a host of other ideas in its “Economic Empowerment” section:

Pay lower-income Black families the equivalent of San Francisco’s median income, currently $97,000, annually for the next 250 years

Create a publicly funded banking institution to grant loans, credit, and financing to those who fall outside the requirements of private banking

Create a publicly funded and comprehensive debt forgiveness program that clears all Black residents of student loans, personal loans, credit card debt, and all other debts

Grant Black individuals tax abatement on sales taxes for the next 250 years

Publicly funded home, rental, and commercial insurance guaranteed for eligible Black residents

Remove credit score ratings from public banking institutions

All government buildings being leased or sold in the city must pay a minimum 50% of their gross receipts into an SF Reparations Fund

Reparations are exempt from all state and municipal taxation

Convert public housing units into condos to sell to Black residents for $1

Make all residential properties vacant for over three months “immediately available” to all Section 8 voucher holders and reparations recipients

While it is currently unknown what the total cost of a full implementation of the committee’s recommendations might be, an economist is not needed to figure out that the city would likely face immediate insolvency with the implementation of these proposals. Some estimates of the cost of the Committee’s recommendations for $5 million payouts sit north of $100 billion—which is more than a third of the state’s entire tax budget. San Francisco’s $14 billion budget, meanwhile, is around seven times less than the price tag of the $5 million payout goal of the reparations agenda.

Are San Francisco administrators crazy enough to do it? Part of me says no way, but anything is possible.