Quick review of Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket

A few ideas inspired by a work of art

Recently started watching Stanley Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket, which is amazing so far despite being a war movie. As a rule war movies are difficult to make believable and narratively compelling—it’s all the same gray waste usually, the same despondent seashores and broken young men strewn across them. It’s boring, it’s pretentious. They’re humorless when they don’t have to be. Young men aren’t humorless, they can always laugh among themselves. In the worst famines in history I’m certain there were endless feasts of sarcasm, steaks and stews and sauces made of the choicest cuts of wit. Most war movies exist in some backward plane where this isn’t the case.

I’m only a third of the way through, but some moments early on were striking so I wanted to synthesize a few details, expand on a few old concepts and apply them in some new ways, and maybe develop some entirely new ideas that might prove useful later on in other work and writing. I plan on watching the rest of the movie in short spurts throughout this week and next, so I’ll do a follow-up review or a full one when I’ve reached the end.

You’re going to war

The movie is set in the Marine Corps Recruit Depot in South Carolina and follows the basic training of a group of recruits during the Vietnam War. The movie filters the harsh development of wartime psychology, which is mediated by the shouting, slandering, and funny drill instructor, Gunnery Sergeant Hartman, through the experience of two recruits Hartman nicknames Private Pyle and Private Joker. Private Pyle is an overweight, mentally unfit recruit named Leonard Lawrence, Private Joker, a flippant recruit named J.T. Davis, is Leonard’s better counterpart, eventual squad leader, and semi-acquaintance.

The recruits get publicly assaulted together, they get verbally abused and humiliated together, they sleep and wake together, they march and run and sing songs together, the songs they sing are about obedience and loyalty, they clean their weapons together, shoot their weapons together, get punished for each individual’s mistakes collectively, and all of this done at the direction of Hartman. There is only one will, the will of Hartman, who represents the will of the Marine Corps. The recruits train their bodies often, but the most essential training is on their minds. There’s a concerted effort by the Corps to depersonalize its members thoroughly. This much is obvious, what isn’t obvious is why this is necessary for fighting.

Wartime, depersonalization, and ideology

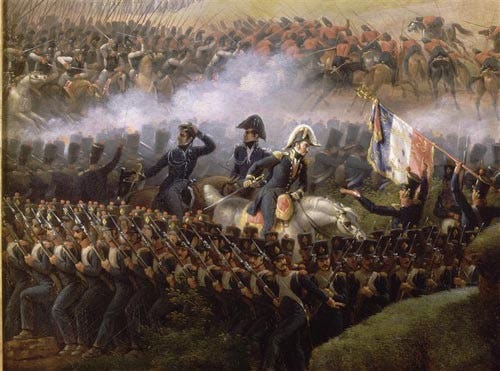

When you think of military training you think of abandoning personhood for assimilation into something like a super-consciousness, which is implied in the word “corps,” derived from the Latin “corpus,” “body.” A group united as one whole, with one goal. Interestingly enough, Napoleon I was the one who invented the concept of a military corps, a self-sufficient army division among several other self-sufficient army divisions. The idea can be explained by another idea from the world of investing: dollar cost averaging.

One way to hedge risk in investing is to make small purchases of an asset over a moderately long period of time. That way any fluctuations in market prices are evened out instead of fully absorbed by your position. You get a total investment that captures the best, the worst, and the middling turns in the market, as opposed to being stuck in one of the three possibilities by making one large investment at one time.

The military corps is the dollar cost averaging of warfare, and Napoleon conquered the world and shaped history by way of it.

Instead of throwing your calvary, your infantry, your artillery, and everything else at your enemy at once, and potentially losing one or more branches permanently, the corps divides, for example, an army of 300,000 men into six discrete armies of 50,000, each with its own command structure and branches. You lose one calvary, you have five more that prove successful somewhere else on the field. You don’t lock your total investment of men into any single turn of fate. Smart.

Napoleon’s innovation of the military corps wasn’t the advent of the notion of corpus, the collective body, but it did put an apt name to an apt place. A military is a supermind, a corporation in the business of bodies, living and dead ones. In a corporation you don’t have personhood, you have the group, you’re everyone in it. What differentiates one individual from the next are goals, what blurs one individual from the next are goals, which is interesting.

A rough psychological analogue of this idea is self-selection. Individuals with one hobby or goal tend to share many other hobbies and goals. Shared goals are what make people similar, different goals are what make people different. The corps depersonalizes its members until they have one goal, until they’re all the same person. In war this likely serves the purpose of mitigating fear of death. As far as I can tell, what makes death such a terrifying prospect is that all the desires in your mind reach a permanent terminus. Your dreams for your children, your wife, your siblings, your parents, their futures, you can’t pursue any of it if you’re gone.

But members of a collective have one goal. If your brothers-in-arms die, it’s as if they hadn’t so long as you’re alive, their dreams were identical to your own, no individuation exists. If you die in the corps it’s as if you hadn’t, as Hartman says, “Most of you will go to Vietnam. Some of you will not come back. But always remember this: Marines die. That's what we're here for. But the Marine Corps lives forever and that means you live forever.” He’s right.

Corps and ideology

Another thing that struck me was how similar military indoctrination is to the basic demands of most ideologies. The one thing almost every ideology demands is to substitute your natural goals, the ones that would arise in you as you go through life, with their own. Any substitution of your goals for someone else’s is a kind of depersonalization. I’ve always wondered why I’ve been disturbed by espousers of ideology, communists and such, and this is why.

Ideology asks for your soul, which sounds terrible to me, but at the same time I do understand why some give it up. There’s a nontrivial subset of people who are burdened by themselves. Their own desires are a “care,” as Jacob says of his wives and children to Esau. They don’t want to deal with them, they don’t know what to do with them, they don’t know how to make what they want a reality. Most of us don’t, most of us are alright with that and settle for a bit less while grinding to get a bit more. They can’t handle imperfection. They assimilate themselves into a military of ideas.

These people cause a lot of trouble, but it’s only fair to try to build some conceptual model for them. I’m sure Schmitt has done this already, and I’ve been reading him a lot lately, but I’m going to have to read more to see.

End

To end with I’ll share something insightful I saw on Twitter that puts a corps into an interesting perspective:

One of the best arguments against AI alarmism is also one of the best illustrations of how a corps is a kind of super-organism. The argument goes:

“We shouldn’t be worried about super intelligent AI!”

“Well, why not? How do you suppose we control an organism several million times more intelligent than us, that can achieve any goal it sets its mind to?”

“Because we have organisms several million times more intelligent than us that achieve any goal they set their minds’ to already!”

“That’s funny. And that would be, what?”

“Large scale enterprises. Groups of thousands of minds working toward narrow aims that in some cases have completely terraformed the planet in pursuit of those aims. Other corporations check their power, eventually.”

Or something like that. A military is a mind, a mind with a gun.

Not sure that large corporations are a good analogy for AI. There is nothing intelligent about large scale organizations: they tend to lose ground to smaller, more nimble competitors unless the large corporations are propped up by government coercion in the form of monopoly privilege or expensive regulatory moats.