Being Decent Is Surprisingly Difficult, But Not Anymore!

Decency is complicated. Sometimes compassion can end up being a waste of time and money, and can even contribute to harm. But after thinking through it, I believe I’ve finally sorted it all out.

Time Well Spent is a reader supported publication, if you’ve enjoyed any of the content found here, consider becoming a paying supporter.

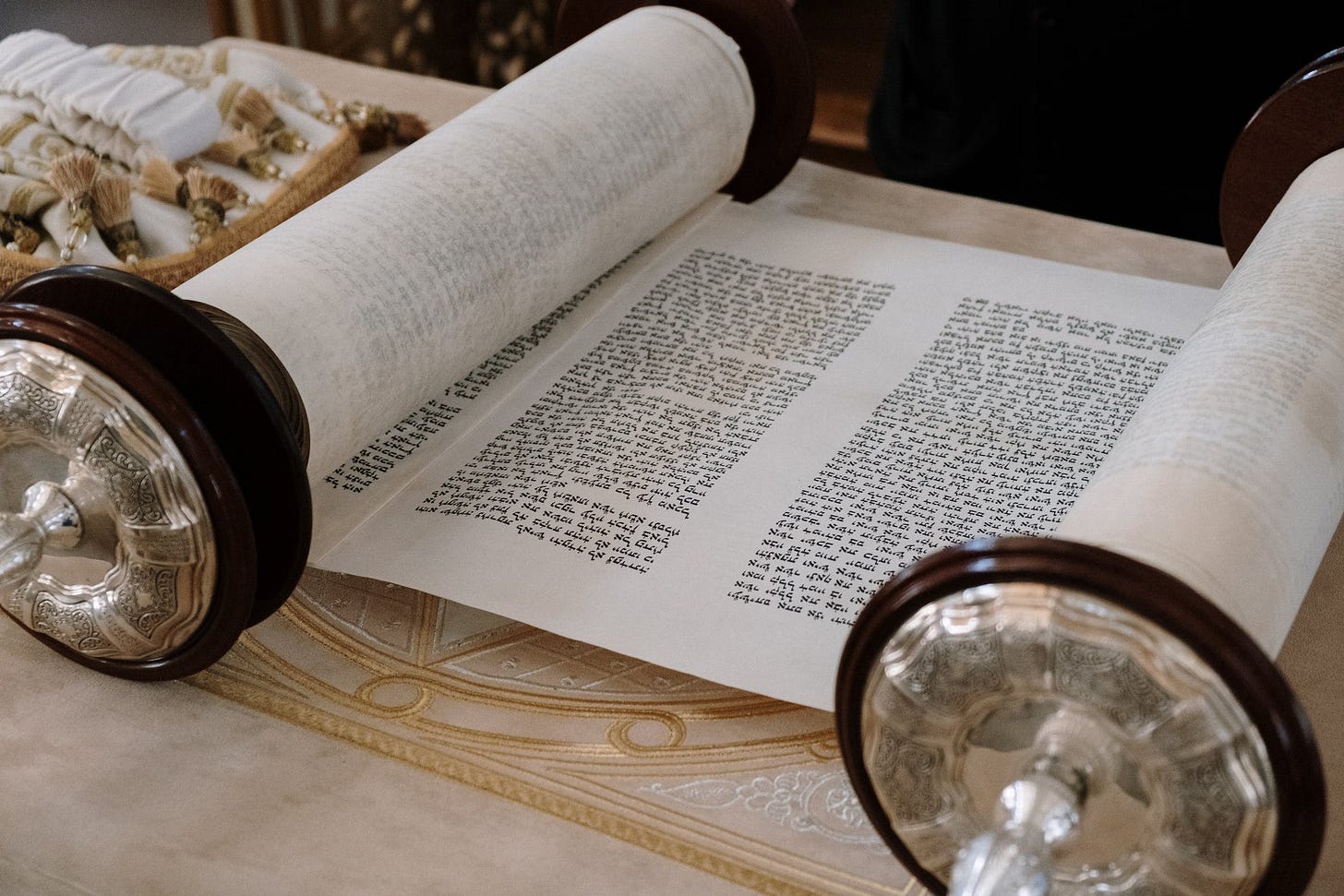

An underrated moral quandary that I’ve been trying to unravel the last few months is how to be a generous person, and it’s really not as easy as intuition may make it out to seem. Since Hanukkah has arrived I thought it would be a good time to dive in and talk about the Torah view of generosity, the modern, everyday view of the matter, and some conclusions I’ve drawn after thinking about it all a bit.

Some of the biggest ethical imperatives in the Torah are the ones about helping other people, especially the poor, the orphaned, and the widowed, besides one’s own kin. Fulfillment of this obligation usually happens through dispensing either food or interest free loans, but there is an overarching subtext of general openhandedness. Taking the Torah’s prescriptions, I first considered giving out cash to the homeless around my county, as most people think to do when they imagine ways to return whatever good has found them. But nearly 70% of all homeless in the United States have histories of substance use disorders, and this means that generosity isn’t a straightforward ideal, and in fact may potentially contribute to harm and even death.

Giving out food would also run into similar complications since, if those with substance abuse issues couldn’t subsist on the generosity of strangers, they may be incentivized enough by their situation to make a change and seek help. Taking this incentive away by providing food without requiring any modified behavior really doesn’t help anyone. It’s a hugely under-discussed problem how drugs have ruined tens of millions of lives, and take tens of thousands more every year. They completely undermine compassion, and I honestly hate them. They make a non-trivial share of the enterprise of individual generosity a null effort, and institutional generosity is also not unaffected, as I found later:

I considered donating to food banks, and I did donate to the one in Los Angeles for a while, but after thinking about it I realized that they had some of the same issues mentioned above, but they also have the added problem of abstracting the charitable individual from any involvement in someone else’s life, they remove the need to actually care about anyone personally. And you may disagree, but I’m not a huge fan of compassion that doesn’t actually involve any obligation on my part, which is one of my main gripes with the whole project of small L liberalism. There are self-styled activists everywhere who talk a huge game about how much they care about blacks and Hispanics and whoever else, and speak on behalf of these groups any chance they get, but who don’t actually go out to these communities and never will, who don’t know anyone from these communities and never will. Their compassion takes the path of least resistance and that’s not really compassion, it’s just well-marketed narcissism. I hate that.

That leaves the people in our lives, most of whom probably aren’t homeless or jobless, but everyone could use a bit of extra cash. We have siblings, friends, wives, girlfriends, etc, so many people in our networks to cashapp or Venmo like an aunt on her favorite nephews’ birthday. And I did shoot some people some cash, but let’s be honest, how many times in a year do we spend our money on things we don’t need, or on things that turn out to be useless toward the fulfillment of some need? It happens all the time, it’s the default state of affairs for most people, including myself. Clothes that don’t look good even though we need new ones, appliances that aren’t exactly what the Amazon reviews described, food that wasn’t as great as what yelp told you. It’s an endless drama of disappointment and a total waste of money, and I know now that that’s where my money was going. There are billion dollar industries that subsist on a high volume of slightly bad financial decisions, companies that sell fake algae and duck fat face-masks to unsuspecting women for example. By giving cash out randomly I probably helped one of these sham companies out, or my money was likely wasted elsewhere!

A big idea in the Torah is that certain actions carried out in our lives will be repaid to us “measure for measure,” though not exactly measure for measure since certain good actions have positive asymmetries. A little bit of Torah study and mitzvot observance, and God rewards the individual and his descendants by making them well-liked and wealthy. His enemies fall before him, his children will be served by kings and princes. And even more goodness is showered on the head of one who is open-handed and who satisfies the needs of others. There are stories in rabbinic literature that illustrate the merit of this, and my favorite one goes something like: Rabbi Elazar ben Parata was sitting in jail after being arrested on five separate counts. He complained to his cellmate, Rabbi Hanina ben Teradyon, that he was much less fortunate than him since the latter was only arrested on a single charge, the charge of teaching Torah publicly. Rabbi Teradyon replied that this was not so, that Rabbi Perata was in fact much more fortunate than himself since, despite being charged on five counts, Rabbi Perata was being set free because he engaged in Torah study as well as acts of kindness. Teradyon on the other hand engaged in Torah study alone and must remain imprisoned despite his single charge. But what does kindness here mean exactly?

A decent book I’ve been reading about this all lately is called Ahavath Chesed by a really great rabbi called Chofetz Chaim. Ahavath Chesed means loving-kindness, and the book is about ways to perform acts of charity and the rewards for doing so. Some of the rewards include being granted an extraordinarily long lifespan (as Chofetz Chaim himself had, living to the ripe old age of 95), and having one’s own needs guaranteed irrespective of whatever one does, and a lot more. Chofetz Chaim describes a flow of goodness that goes far beyond the rewards for engaging In Torah, and personally I want that extra portion of goodness. But even after reading this book the path toward actually helping other people remained unclear to me. Chofetz Chaim proposed that giving loans out was the highest form of charity, but we’ve already seen that, because we often don’t know the best way to deploy capital to our own benefit, money isn’t always the best way to satisfy others’ needs. But after thinking about it a bit more, I realized that “needs” was a key word, that it more or less contained the entire object of the pursuit of decency. The best thing you can do for someone, I realized, wasn’t to just throw money at them and hope for the best, it’s to ask them what they need or find out by being a friend, and satisfying that need for them directly.

Sometimes the need has absolutely nothing to do with money at all. For example, so many people really just need someone to talk to, someone to discuss their problems with or bounce creative ideas off of. Sometimes they don’t know how to resolve their chronic boredom and need to be introduced to a movie you’ve thoroughly vetted for them or a book you know they’ll love. Sometimes they need kind words and a show of support to soften the blow of family or other relationship troubles. Sometimes they need positive feedback and a consistent flow of encouragement on some creative or other venture that you know will eventually pay off. Sometimes they need to be introduced to the right people to help their business ideas develop and flourish. Sometimes the need barely costs a thing. Maybe they work from home and get terrible echos during zoom calls, so you just buy them a carpet for a few bucks to deaden the sound and get rid of the echo. Sometimes the need costs a bit more: let’s say someone tends to sleep very late but barely rests at all because the morning light breaks in like a burnished intruder, waking them early, and you buy them some blackout curtains to extend the night well into the day.

So many needs, so often overlooked by misconceptions of charity and compassion that I’ve had. A whole world of generosity has yawned out in front of me since this realization and it feels so amazing to finally be able to help in ways that are deeply impactful. To return the good that’s found it’s way to me. And now hopefully you can return some of the good that’s found its way to you, too.

The concept of tzedakah (sadaqah in arabic as voluntary additional deed to zakat 10%) sets out works of charity from least to most meritorious, the most being -Enabling the recipient to become self-reliant. It seems that most western forms of charity are set up to enable the administrators to be self reliant. Charity watches look for the admin spend of charities when they should be balancing that against outcomes that enable fewer people to seek succour from their charities. Which is why community level direct intervention (help a family, help a person) is FAR more impactful than any and all charity giving. Problem is Charities are like Madison Ave offshoots now-the slickest marketing gets the bucks...