Americans Are More Offended By Nazi Germany Now Than Americans Alive During WWII

Nazi Germany takes up outsized space in contemporary frameworks of good and evil. Of all the terrible governments in history, from Pol Pot’s Cambodia to Mao’s China to Lenin’s Soviet Russia, the Nazi party gets first priority in popular political and moral philosophy. You’re either a good guy, or you’re a Nazi.

The word is mostly used to inject a kind of MCU (Marvel Cinematic Universe) energy into discussions about political opponents of progressive Americans. Hollywood has done a good job taking the Nazi’s from their natural status as just another horrible regime in history and exalting them into the something much more.

They’re the archetypal enemy, the final boss, actions that are no holds barred are required to defeat this legendary villain, which naturally makes you the equivalent of a superhero. The word now conveys that someone is so dislikable, it’s sensible to center your entire life and personality around opposing them.

But Americans during WWII felt much different about Nazi Germany, and I was honestly surprised when I found out recently. I’ve always assumed what Hollywood told me was correct, I’ve watched Inglourious Basterds a dozen times, Americans alive during the outbreak of the war were willing to be invested in it, right? Wrong.

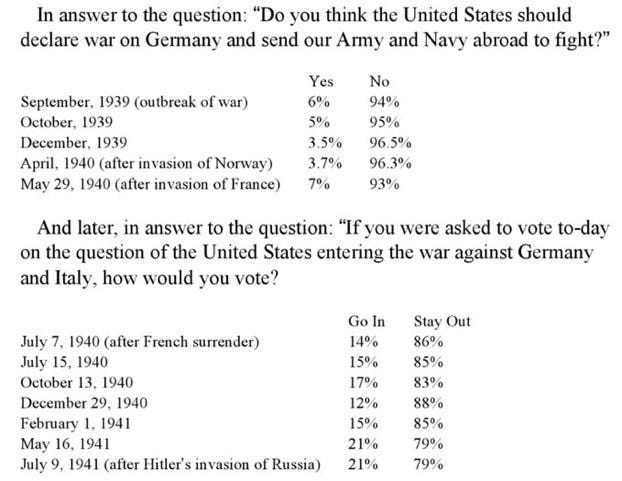

Americans completely disapproved of US entry into the war all the way through to its end:

Pre-WWII US was an isolationist nation, which is a very different nation from the one we’re living in now. Germany wasn’t an existential threat in the popular US imagination of the time, the war made little sense insofar as US involvement was concerned. It’s unbelievable to imagine how far things have changed, how different Americans have become.

But this is why history is so cool. There’s no other way to gain real perspective!

Here’s an excerpt from the book The Tragedy of U.S. Foreign Policy: How America's Civil Religion Betrayed the National Interest, describing the sentiment at the time:

"The war as a necessary evil has been soberly accepted and squarely faced. But it is not a crusade as such as we saw in 1917." Isaiah Berlin thus realized early on what author Studs Terkel later documented at length: World War II was not a good war at all in the minds of Americans. On the contrary, their mood was bitter, stoic, grim, impatient, and vengeful. Nor was it fought by a "greatest generation," if that phrase meant anything more than unlucky. The home front did not display a uniformly patriotic team spirit.

Widespread cheating on rations, absenteeism, profiteering, draft dodging, and malingering distressed the War Production Board and even the president. Overseas the GIs were often sullen and risk-averse, a mood amply documented by Studies in Social Psychology in World War II. The American Soldier, made under the direction of sociologist Samuel Stuffer for U.S. Army chief of staff George C. Marshall. Enlisted men understood that Pearl Harbor meant war and that once in the war, the United States had to win. But two-thirds of them suspected the country had been dragged into it by big businessmen and imperialists. Just 15 percent interpreted the conflict in terms of moral goals like destroying fascism or securing the Four Freedoms (which the vast majority could not name). Soldiers were skeptical of all propaganda, including their own, which meant Roosevelt could not effectively recycle Wilsonian calls to make the world safe for democracy. Moreover, the servicemen were well aware that a U.S. victory also meant victory for the British Empire and the Soviet Union, both of which they deeply distrusted.